- Document History

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report to a Moderator

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report to a Moderator

This is part of a series of recommendations on how to implement some of the famous Gang of Four OOP design patterns using LVOOP. It represents an open discussion with the NI Community, so please feel free to provide comments and suggestions if you have any!

Intent

Change the behavior of a class's method without having to edit the method's implementation. Change a method's behavior dynamically, at run-time. Allow future expansion of a method's behaviors via a plug-in framework.

Motivation

Your class performs one or more actions differently depending on a configuration parameter, or on an initialization option when its objects are instantiated. You could use inheritance to create a general parent class and child classes for each possible set of behaviors, but only some methods share the same behavior among classes, and future children may not want to implement some of the parent class's methods. Instead, use your class contain a family of classes that each define a set of behaviors for some of your class's methods.

Implementation

see strategy_pattern_lv85.zip

[Note: Paul Lotz graciously contributed a more spiritually accurate example of implementing this pattern. It is attached as "CookingStrategyPatternBasic.zip".]

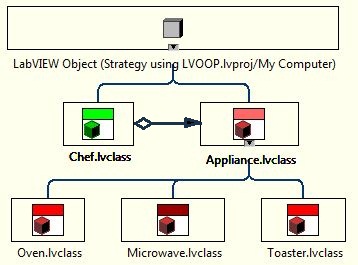

This pattern depends on composition to encapsulate the parts of a class that may change. The class you want to define is a Composition, and the methods/data that may vary within it are broken out into a separate family of classes called Compositors. In LabVIEW, a general parent compositor is used to house all the concrete compositors that may be defined. (In other languages, this would be handled using an abstract class or an interface that each concrete compositor extends/implements.) You can then add new concrete compositors to that hierarchy without having to modify the hierarchy of your compositions.

Here is a cooking example to illustrate the concept: A Chef.lvclass needs to make dinner and has at his disposal several methods of doing so. The details of how each method is implemented (the algorithm for each method) will change depending on which cooking appliance he wants to use. Rather than define subclasses for each appliance -- ToasterChef.lvclass, OvenChef.lvclass, etc. -- a separate Appliance.lvclass is defined, and children are instantiated beneath it. The Chef.lvclass is then passed a concrete Appliance.lvclass as part of its private data. It holds this appliance object, and when it is asked to perform a cooking method (like Broil.vi), it calls on the same method within the appliance. The appliance handles the method using its particular algorithm. Later on, the Chef may switch to a different appliance that can handle the Broil.vi method in a different way.

In this example Chef.lvclass is also called a context, and the application that instantiates a chef object is called a client. Appliance.lvclass is a strategy, and its children are concrete strategies.

Consequences

Strategy allows you to define a family of algorithms that can be exchanged by a context at runtime. Instead of using Case Structures in methods that may vary to decide which behavior they will exhibit, you can use dynamic dispatch to make that decision based on the concrete strategy in use. Unlike simply subclassing the context to overrides its methods, however, Strategy lets you vary the algorithm dynamically without destroying and recreating the context.

Each family of algorithms -- in the example above, Appliance.lvclass and its children -- can also be reused in multiple contexts. You may later create a Sous-Chef.lvclass that also wants to use these appliances in the same way as Chef.lvclass. With Strategy, you only have to add an instance of Appliance.lvclass to the sous-chef's private data in order to reuse those algorithms.

Implementing Strategy often increases the number of objects in an application. You can usually minimize this effect by having each context manage all state information, instead of putting state into the concrete strategies that could instantiate several objects each.

In many cases, the client will decide which strategy its context uses. This requires that the client be aware of the strategies available to its context and the tradeoffs between them. If possible, provide a behavior-switching interface in the context that removes this responsibility from the client.

Editorial Comments

[David Staab]

Although there are no abstract classes in LabVIEW, Appliance.lvclass is treated as one in this application. Its role is simply to act as a type definition, in the computer science sense, for any concrete appliance (Oven, Microwave, Toaster) so the Chef doesn't have to know which appliance it will use at compile-time. Subclasses can be required to override a method by selecting the "Require descendant classes to override this dynamic dispatch VI" option on the Item Settings page in the Properties dialog. For methods that may be only optionally overridden, the methods defined in Appliance.lvclass can be written either no-op or provide a default behavior.

This example also defines a constructor method to avoid letting one of Chef.lvclass's methods try to call on a null object. Constructor methods are classically required to execute when an object is instantiated, and they are not defined for LabVIEW. The workaround used in this example is to define a data member -- a Boolean called "Constructed" -- that each method checks to make sure the object's constructor method has been called first. The constructor method sets the data member when it is called, along with any other standard instantiation procedures that need to take place.

Strategy and Delegation

It's easy to look at the Strategy pattern and think you're looking at an example of delegation. In fact, you are: delegation is a technique employed in object-oriented programming. Many design patterns employ that technique to increase an application's reusability and extensibility. Strategy is one of those patterns. By delegating the varying algorithms in a class to a composed abstract class, you can let children of that abstract decide which algorithm to employ at run-time.

Staff Systems Engineer

National Instruments

- Mark as Read

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Permalink

- Report to a Moderator

Incidentally, this is a form of dependency injection, an extremely powerful technique that is harder to implement safely without using objects.

The Chef-Appliance example is useful for illustrating the pattern, but it may be hard for people to understand how the pattern can help in their own code. Here's how I recently used the Strategy Pattern to solve a real-world problem. (To avoid drowning in technicalities I'll leave out a lot of the exact implementation details.)

In my job a lot of our tools have to parse and filter a complex, multi-layered, device communication protocol. To make it as easy as possible for other users to import parsing functionality into new apps, I decided to create a 'PacketFilterSlave' class that enapsulates all the parsing functionality in a separate loop (though this isn't an Actor/Active object, for those who are familiar with that design.) I defined two simple messages the object accepts and acts on: ExitFilterLoopMsg and FilterDataMsg. I also defined a set of response messages that return filtered data and update the master loop of the slave loop's status, such as PacketFilterDataMsg, PacketFilterExitingMsg, and PacketFilterErrorMsg.

The problem is that each application has different filtering/parsing requirements. How can the filtering be customized without editing the PacketFilterSlave source code? That's where the Strategy Pattern came in.

I created a FilterInterface class that defines a single method: ExecuteFilter. This method has an input for accepting unfiltered data and an output for returning the filtered data. When the PacketFilterSlave.FilterData message is sent from the master loop, PacketFilterSlave passes the unfiltered data into FilterInterface.ExecuteFilter. App developers customize the filtering algorithm by creating their own Filter classes that inherit from FilterInterface and override the ExecuteFilter method.

These two classes are packaged in a lvlib and can be imported into new projects by simply copying the folder to the new project. Adding robust and flexible parsing capability to any application is a snap. The PacketFilterSlave class handles all the messaging and other overhead associated with managing an independent loop. The app developer can focus on creating and testing the actual parsing algorithm instead worrying about implementing slave loop management.

- Mark as Read

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Permalink

- Report to a Moderator

This example doesn’t quite capture the point of the Strategy Pattern, actually.

What would be better is to create a "BroilBehavior" abstract class, and then implement several subclasses that implement different ways (algorithms) to accomplish the broiling (e.g., a "broil" method).

Appliance can include "BroilBehavior" in its private data (i.e., have a reference to it) and when you instantiate an Oven, Microwave, or Toaster object you can add the appropriate BroilBehavior type. (Note that multiple appliances can in principle use the same broil strategy, and a possible broil strategy can be to do nothing.) Cook invokes Appliance:broil, i.e., and Appliance delegates to the BroilBehavior:boil class method. The actual method that executes will depend on the type of BroilBehavior. Effectively, then, we are programming to an interface.

One advantage to this is that if more than one appliance uses the same broil behavior (e.g., don't broil), we only have to write the code for this once (rather than in each appliance), and if we need to change that behavior we only need to change it in one place.

(Perhaps a better example still is to have CookX strategy, and the different algorithms can be to broil, bake, or so on.)

The key here is to subclass the algorithm (behavior) rather than the actor (client) that uses the behavior. (The direct client of BroilBehavior should be Appliance, not Chef, if we are talking about varying the algorithm implementation.)

The example is perfectly valid, by the way (thanks to the author for sharing it!)—it just doesn’t illustrate the intent of the Strategy Pattern well. It does provide a good prompt for discussion, which is the point of the forum!

- Mark as Read

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Permalink

- Report to a Moderator

I agree, and I created the original. ![]() Any chance you can whip up the new example and serve it to us in a comment?

Any chance you can whip up the new example and serve it to us in a comment?

Staff Systems Engineer

National Instruments

- Mark as Read

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Permalink

- Report to a Moderator

Can anyone envision using this pattern (with other patterns possibly) to build a hardware abstraction layer? What I see there is a that you have an appliance (your hardware) that could possibly have a common interface (i.e. all pieces of hardware get some data) but how they implement that interface differs considerably (based on factors such as communication platform, model, etc. etc.). I am just starting to think about this so maybe I am way off base. Matt

- Mark as Read

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Permalink

- Report to a Moderator

Matt,

I don't think you are off base at all. I don't use HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layer) terminology (mostly because I am thinking about this a little differently, and maybe because I don't know that much about HALs), but I would think the way Appliance:cook() works in my CookingStrategyPattern example is along the same lines.

Paul